Abstract

The mechanisms leading to clinical progression of CLL from early asymptomatic stages are not fully elucidated, being the acquisition of molecular alterations an infrequent phenomenon. Abrogation of autologous immune response against neoplastic processes is a key feature defining cancer. In CLL, malignant cells are able to evade immune anti-tumoral responses through inhibitory ligand signaling and defective immune synapse with T cells, which in turn exhibit an impaired proliferation and cytotoxic activity as well as high expression of exhaustion markers. In addition, other immunosuppressive features, such as production of IL-10 by CLL cells, are observed in these patients. Against this background, we hypothesize that evasion from immune surveillance is a mechanism of clinical progression from early stages in CLL that potentially opens a new field of therapeutic opportunities.

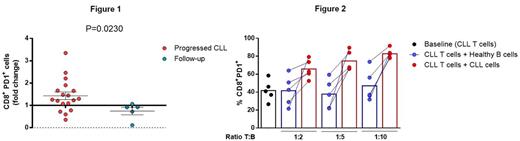

To study changes in the immune system related to clinical progression, we performed flow cytometry analysis in paired samples from 19 patients with CLL at diagnosis and progression (median time to progression: 2.2 years), and in paired samples from 5 CLL patients without clinical progression (median follow-up: 2.7 years) as controls. At progression, we observed a significant increase in the absolute numbers of the CD45RA-CCR7- effector memory (EM) subset in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells; CD4+ and CD8+ EM also had increased expression of PD1 at progression. Of note, there was no increase in PD1 in patients that did not progress; pointing out that PD1 plays a relevant role in CLL progression (Figure 1). Moreover, the inhibitory receptors CD244 and CD160 were significantly increased in CD8+ T cells and the co-expression of these receptors was also significantly higher in CD8+ cells at the time of progression. Differential expression of the transcription factors T-bet and Eomes defines the progenitor (T-bethiPD1int) and the terminal (EomeshiPD1hi) exhausted CD8+ T-cell subsets. In CLL, the EomeshiPD1hi CD8+ terminal subpopulation was significantly increased at progression, whereas the T-bethiPD1int CD8+ progenitor subset was stable, indicating the predominance of a more severe exhausted subset. In addition, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) were significantly increased and NK cells were decreased at late stages, while in contrast regulatory T cells remained unchanged. To further evaluate the increase of immunosuppression during progression, we studied IL-10 production in paired CLL samples. After 48 hours of microenvironmental stimuli, expression of IL-10 by CLL cells was significantly higher in samples obtained at the time of progression. In agreement with this, IL-10 plasma levels were higher at progression (n=9 pairs). This enhancement of regulatory B cell properties in CLL cells may also contribute to the increase of exhausted T-cell phenotype observed at clinical progression. To study the influence of B-CLL cells in T cells, we modeled progression in vitro by co-culturing T cells from CLL patients with increasing ratios of autologous CLL cells during 7 days. Under this setting, CLL cells induced a higher expression of PD1 (Figure 2) and CD244 in CD8+ T cells compared to healthy B cells, this increase being dependent on the T:B ratio. To evaluate the contribution of IL-10 to the induction of T-cell exhaustion in vitro we are currently blocking its production from CLL cells and these results will be ready at the time of the meeting. Finally, to rule out the putative contribution of genetic clonal evolution on CLL progression, we analyzed by deep sequencing (median deepness of 16000X) mutations in 8 driver genes (MYD88, NOTCH1, SF3B1, BIRC3, TP53, XPO1, ATM and POT1) and the size of the subclones affected at diagnosis and progression. Out of the 17 cases analyzed, we found driver mutations at diagnosis in 10 patients, from which only one showed clonal evolution at progression (increased allele frequency in SF3B1 and ATM mutations).

Taking these results together, we conclude that clinical progression of CLL is potentially driven by an increasingly severe exhausted T-cell phenotype and by an enhancement in immunosuppressive features such as accumulation of MDSCs and elevated IL-10, pointing towards an impaired anti-neoplastic autologous immune response as a main mechanism of clinical progression. These results support the design of new immunotherapeutic strategies for patients in early stages that are likely to progress.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal